When it comes to the nude in art, there is simply too much to cover in one conversation. The nude has been represented throughout art history, from early primitive goddess statues, to the marbles of Ancient Greece and Rome, through to the Renaissance and Modernity. What is interesting, is how contemporary morals and ideals of beauty have coloured the way in which the nude has been depicted.

The one common thread, particularly before the 1950s, is that the female nude has always been depicted looking generally flawless - smooth skin and definitely no hair down there! This notion that pubic hair is somehow too offensive to depict continues in many mainstream nude representations today and general audiences tend to find realistic nudes a bit too indecorous to hang on their walls.

British art historian, Kenneth Clark, wrote a well-respected book on the history of the nude in art in 1956 The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, in which he made the distinction between the naked body and the ‘nude’. Clark noted that nakedness related to being without clothes, with connotations of embarrassment and shame, whereas the nude in works of art are considered ‘high art’, above the usual embarassment and self consciousness that surrounds the raw state of nakedness.

The one common thread, particularly before the 1950s, is that the female nude has always been depicted looking generally flawless - smooth skin and definitely no hair down there! This notion that pubic hair is somehow too offensive to depict continues in many mainstream nude representations today and general audiences tend to find realistic nudes a bit too indecorous to hang on their walls.

British art historian, Kenneth Clark, wrote a well-respected book on the history of the nude in art in 1956 The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, in which he made the distinction between the naked body and the ‘nude’. Clark noted that nakedness related to being without clothes, with connotations of embarrassment and shame, whereas the nude in works of art are considered ‘high art’, above the usual embarassment and self consciousness that surrounds the raw state of nakedness.

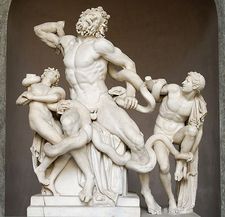

When you look back to classical times (4th C BCE and on) and the beautiful, idealised marble statues of both men and women, they are generally portrayed as hairless and are very perfectly formed characterisations. They are not erotic, but rather romantic and physical manifestations of the greatest ideals and achievements of humankind, hence the immortalisation of athletes, warriors, philosophers and gods.

There are however a number of classical statues that do show decorative pubic hair and others were painted on in brown, long since faded. Curators of centuries passed, chose not to restore these in the interest of the public.

There are however a number of classical statues that do show decorative pubic hair and others were painted on in brown, long since faded. Curators of centuries passed, chose not to restore these in the interest of the public.

In contrast, outside of traditional Western art discourse, early prehistoric female nude figures, known as Venus figurines, celebrated female power and fecundity. In India, temple sculptures and cave paintings celebrated human sexuality and the Kama Sutra, and Japanese woodblocks prints (Shunga Ukiyo-e) offer a long history of sexual activity with highly exaggerated sexual parts.

It was the rediscovery of classical culture during the Renaissance that brought the Nude back into popular art. The David, so beautifully rendered by Michelangelo in 1504, is one of the most striking marbles of the Renaissance – he is muscled, smooth and surprisingly has genital hair. During this period, men were generally portrayed as virile and active. However, Western depictions of women were more passive and often women became an object of voyeurism under the guise of religiosity.

The Renaissance is probably most often associated with the traditional versions of the female nude we are accustomed to seeing – think Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1486) painted for the Medici family, which shows a highly idealised nude Venus coming out of a clam shell. She is very white and pure, reminiscent of a classical marble - smooth, flawless, hairless and beautiful, the perfect ideal of 15th C feminine beauty in the acceptable form of a goddess.

The Renaissance is probably most often associated with the traditional versions of the female nude we are accustomed to seeing – think Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1486) painted for the Medici family, which shows a highly idealised nude Venus coming out of a clam shell. She is very white and pure, reminiscent of a classical marble - smooth, flawless, hairless and beautiful, the perfect ideal of 15th C feminine beauty in the acceptable form of a goddess.

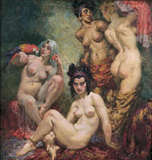

Leading up to and during the Baroque period (17th C), the fascination with the classical nude continued, however, artists began to work more frequently with live models. The more fleshy nudes of Rubens for example, although still hairless, show cellulite and stomach rolls; a much more naturalistic depiction of the female nude that this art dealer can relate to!

Men remain depicted as heroic mythological and biblical figures showing strength or suffering, such as Hercules and Samson, and the female nude mainly continued to represent goddesses and mythological figures.

Numerous religious works depict very violent and bloody scenes, where nudity is used to highlight the moral compass of the day as well as man’s dominance over women.

Men remain depicted as heroic mythological and biblical figures showing strength or suffering, such as Hercules and Samson, and the female nude mainly continued to represent goddesses and mythological figures.

Numerous religious works depict very violent and bloody scenes, where nudity is used to highlight the moral compass of the day as well as man’s dominance over women.

| And yet, in 1797 Goya painted The Nude Maya, which was shocking in that it was not a nude glorified by a historial or bibilical setting, but a real life model, depicted as herself, nude and with her pubic hair showing. Moreover, as she reclines seductively, she gazes directly and unashamedly at the viewer. Gone are the modest, averted gazes of her predecssors with their diluted sexuality. |

In fact, when the well-known Victorian art critic John Ruskin saw his wife on their wedding night, he was allegedly appalled to discover she had pubic hair as he had never seen such a thing on paintings of nudes! After 5 years, and no consummation, the marriage was annulled.

The direct gaze became an obsession of artists in the 19th century. While academic painters continued to paint classical themes, they were challenged by the Impressionists. Eduard Manet shocked the public of his time by painting his nudes in relatable, contemporary settings. His celebrated work Olympia (1865), highlights the more pared down brush stroke of this period and flaunts the sexuality of the nude model. She is not looking away from the viewer with classical detachment, but directly meets the eye of her audience; a prostitute proud of her body and sexuality and explicitly erotic. Several items indicate her identity as a prostitute, including the orchid in her hair and the oriental shawl on which she lies, showing wealth and sensuality.

While audiences were accustomed to nostalgic and romantic depiction of the nude, being confronted by a real person, in a modern setting, was highly controversial. Although her private parts are covered by her hand, this may have been perceived as drawing more attention to it. Yes, that old chestnut.

| This was a period of revolution in the depiction of the nude, which perhaps culminated with Gustave Courbet’s Origin of the World from 1866, which shows a naked female from mid-breast to the top of her thighs, legs open and exposing a full growth of pubic hair – this is the source of all mankind, showing the true nature of a naked woman, hair and all and utterly exposed. |

There is no innocuous, hairless V shape here. It is believed to have been commissioned by a wealthy Turkish diplomat for his private collection of erotic art and passed through several private collections, eventually winding up in the Musee d’Orsay in 1955. Such a radical work for the time was not painted for mass consumption, rather the private pleasure of an individual art buyer.

This sense of voyeurism, both the model confronting the viewer and the viewer observing the model, is seen in the work of Degas, who frequently painted women at their ‘toilette’, naked and bathing in very private moments. These works must have been titillating to their male viewers at the time and perhaps liberating for women.

When it comes to modern art in the 20th century, the nude has gone through many metamorphoses depending on the school of art in which she was depicted. The Cubists created deconstructed, geometrical forms and Picasso revolutionised distorted abstraction. Egon Schiele painted dark, intimate and sexualised images of women in exposed positions.

Mid-century, Lucien Freud’s works abandonned all sense of idealisation, shopwing floppy breasts and later working with obese models whose bodies were imperfect, realistic and revealing.

When it comes to modern art in the 20th century, the nude has gone through many metamorphoses depending on the school of art in which she was depicted. The Cubists created deconstructed, geometrical forms and Picasso revolutionised distorted abstraction. Egon Schiele painted dark, intimate and sexualised images of women in exposed positions.

Mid-century, Lucien Freud’s works abandonned all sense of idealisation, shopwing floppy breasts and later working with obese models whose bodies were imperfect, realistic and revealing.

In Australia, Norman Lindsey is synonymous with the nude and his use of real life models, confronting the viewer with their direct gaze, were again controversial. He was considered to be perverse by the establishment and in 1940, when his wife took sixteen crates of artworks to America to protect them from the war, they were impounded and burned as pornography by American officials.

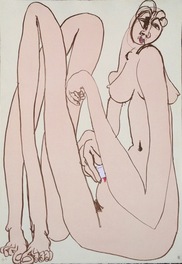

Brett Whiteley’s curvy and sensuous nudes of the 1960s were revolutionary in Australian Art, and while he abstracted the female form, he was not hesitant to include pubic hair for both male and female nudes and several of his explicit works of copulating couples show the influence of the early Japanese erotic ukiyo-e. Whiteley happily embraced the primal sexual urge and sought to record sex and sensuality in his art.

Brett Whiteley’s curvy and sensuous nudes of the 1960s were revolutionary in Australian Art, and while he abstracted the female form, he was not hesitant to include pubic hair for both male and female nudes and several of his explicit works of copulating couples show the influence of the early Japanese erotic ukiyo-e. Whiteley happily embraced the primal sexual urge and sought to record sex and sensuality in his art.

| In 1981, he wrote as part of an art exhibition dedicated to the nude: Filtering down through civilization is the urge to show this glimpse of beauty, where invention and skin become one, and the history of art marries the whole history of one’s sex. Mistress, mother, lover, whore, obtainable –unobtainable, it is the wonder of a perfect distortion. Richard Larter’s 1970s and 80s works turned modern art on its head, with his photographic collages and pop-art paintings considered by some to be blatant pornography – these works leave little to the imagination and the women are highly sexualised. |

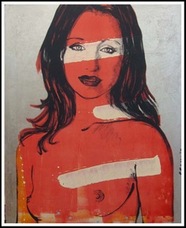

Currently, David Bromley has created a large body of nude works – they are larger than life, however, they are sanitised in that they depict the nude models from above the waste, exposing breasts but nothing more scandalous.

In fact, pubic hair remains a widespread taboo in art today as well as social media. Although moral standards have changed considerably over time, particularly with the advent of photography, cinema and television, public displays of nudity are often controversial.

In 2011, a complaint was lodged against Facebook through the Parisian court of general jurisdiction by a French Facebooker when his profile was disabled for showing a picture of Courbet’s Origin of the World. His lawyer claimed that deleting his account was a breach of his human rights, which should have guaranteed his freedom of expression.

In fact, pubic hair remains a widespread taboo in art today as well as social media. Although moral standards have changed considerably over time, particularly with the advent of photography, cinema and television, public displays of nudity are often controversial.

In 2011, a complaint was lodged against Facebook through the Parisian court of general jurisdiction by a French Facebooker when his profile was disabled for showing a picture of Courbet’s Origin of the World. His lawyer claimed that deleting his account was a breach of his human rights, which should have guaranteed his freedom of expression.

Facebook's rules state users 'will not post content that is hateful, threatening, or pornographic, or that incites violence, or contains nudity or graphic or gratuitous violence.' Little did Courbet know. The company has so far refused to comment on the legal action.

In February, Danish artist, Frode Steinicke, had his Facebook account deactivated for posting a copy of the same infamous painting. Facebook later reactivated his account on condition he only used pictures of clothed people on his page. In reaction, critics have established a Facebook group condemning the censorship of this artwork and art in general.

No doubt, contradictions will always exist as to what is socially acceptable. Towards the end of last year, Instagram banned a user for uploading a nude self-portrait. There are many semi naked or breast revealing images on Instragram including Kim Kardashian's raunchy ‘boob and bum’ pictures. However, the other user had her account deleted because her nude image showed her pubic hair! In fact, she was wearing a pair of briefs and only a sliver of the top of her pubic hair was visible.

It goes to show that in an open forum, genital hair is still a no-no like it always was, but what a thin line we travel.

In February, Danish artist, Frode Steinicke, had his Facebook account deactivated for posting a copy of the same infamous painting. Facebook later reactivated his account on condition he only used pictures of clothed people on his page. In reaction, critics have established a Facebook group condemning the censorship of this artwork and art in general.

No doubt, contradictions will always exist as to what is socially acceptable. Towards the end of last year, Instagram banned a user for uploading a nude self-portrait. There are many semi naked or breast revealing images on Instragram including Kim Kardashian's raunchy ‘boob and bum’ pictures. However, the other user had her account deleted because her nude image showed her pubic hair! In fact, she was wearing a pair of briefs and only a sliver of the top of her pubic hair was visible.

It goes to show that in an open forum, genital hair is still a no-no like it always was, but what a thin line we travel.